For the last seven years, the 4th of July has been the day I looked forward to the most all year. The day always began with our city’s annual parade, where red, white, and blue bedazzled golf carts throw candy to eager kiddos who set up camp on a sidewalk thirty minutes early to get a good spot. Then we moved to my parents’ house on the lake–the little lake house they bought for a steal of a price in 2013 and made into their dream home, where they would retire and watch their grandkids learn to swim in their front yard. We spent the rest of the day there with an open door to friends coming and going, but mostly coming and staying for pulled pork and pasta salad and sugar cookies and lemonade. And of course, jet skis and lily pads and sparklers and s’mores.

Since 2017, almost all of my favorite memories are of this day, those friends, and that place.

Last fall, just before Thanksgiving, my parents sold their little lake house, and found a home up on the hill with enough room for seven more people: me and my six kids. An unfortunate reality of divorce and radically shifting financial situations. I’m one of the lucky ones, to end up with my parents and not in any number of less stable options, and that is not lost on me.

And still, as the 4th of July inched closer on the calendar this summer, I tried to keep my expectations realistic: your friends will make other plans, maybe you can find a generous neighbor’s pool to swim in, and a place to watch fireworks, you can still make muddy buddies and s’mores. As the day approached, we did patch together some plans with friends who knew this would be a tough “first” in the year after divorce for me. Several kind souls reached out to let me know they were thinking of me that morning, offering prayers that even though this day wouldn’t be what it had been for seven years, that it would still be sweet for the kids and me. I prayed the same things. I got ready for the day dressed in my red, white, and blue. I curled my hair, y’all.

And I ended up not even leaving the house.

Instead, I was waging war against autism, absorbing the radical loss of control from a little boy whose mind had betrayed him. It is still fresh and hard for me to put myself back in that scene, knowing it was real, without tears. It was, plainly, the worst day of my life as a disability mom.

//

I went on a long bike ride last night, through the rolling hills of country roads not far from my home, where it is just me and the cows and the birds and the sunset. I’ve been doing this 10-mile loop as a training ride for a few months now, because I love the steady cadence of hill intervals it provides. Riding my bike up a hill has gotten easier, but make no mistake, no hill is easy. Every single one makes my legs burn, my breath heave, and my mind say, “You know you don’t have to do this, Katie, so why are you?”

I’ve learned a few things with each ride that have helped me feel stronger, like only looking a few feet ahead instead of keeping my eyes glued to the top of the hill. The slope doesn’t feel nearly as steep when I look at it in increments. Staring at how far I have to go is much tougher.

But then every single hill eventually goes down, and that’s the best part, the closest I will ever feel to flying. And that’s when I know why I do this. The challenge of the hill behind isn’t forgotten, but I certainly don’t feel the burning anymore, not for those few seconds when the wheels on my bike turn faster than my legs can even keep up, so I don’t have to do anything at all to keep moving, except hold on.

And last night, I went for a ride because I felt really, really sad, and I wanted to feel for a moment like I was flying. I wasn’t even angry when I got on the bike, though I have felt that emotion often in the past year. I was just so sad.

Because I thought the limits of my life raising a little boy with autism were already constraining, but this latest spell of behavior has felt like a rope tightening around our waists, tying us together like hostages to a life we didn’t choose, keeping us from so many things we love. Every time I leave the house with him, my nervous system is on high alert, waiting for the thing–which could be anything: the wrong word from me, the store not having the right juice, tripping over a crack in sidewalk–that sends him into a rage of self-injurious behavior, throwing his head into the nearest hard surface he can find whether that is a random car window or the cement of a parking lot or a large weight-bearing column in the middle of the grocery store. How could this–raising a boy with autism–be getting harder? I silently scream, to God, to myself, to no one in particular.

I have spent the last eight years writing about hope for disability, trying everything anyone suggested could help (this is where you don’t need to wonder whether I’ve bought the supplement/essential oil/weighted blanket/vitamin/detox formula because I have, all of it), doing therapy with him five days a week for nearly every month of his life since his diagnosis, reading all the books and praying all the prayers and preaching all the right things to myself and others, are we really going backwards now?

And then on that bike ride, taking in, for a few moments at least, a picture perfect world that I know God made–golden light dancing over the top of slowly swaying grass, baby quail birds running after their mama across the road, nothing but quiet for miles–it hits me. I am so sad that I have crippling anxiety when I walk out the door and leave Cannon home, afraid of what could happen while I’m gone. And I’m sad that I have even more anxiety when I bring him along, terrified of what could happen in public. I am sad about the five things I canceled this week alone, because I didn’t want to miss them but I couldn’t bring myself to attend either. I’m sad because the challenging reality of disability revisits me fresh every single day. And I’m devastated that I don’t have a partner for life in this anymore.

But mostly, this is why I’m sad: because there is not one atom in my body that thinks the world is one big cosmic mistake, or depending on your disposition, wildly unlikely good luck. That we are all just here by random happenstance, living for a few years and then dying and if we are hashtag blessed, living a life of a least moderate privilege while we are here. It’s quite the opposite. I know God is real, that Jesus is who he says he is, and that the rescue of my heart is a miracle. And that is why I’m sad.

I’m sad because God is real, and the desperate prayers of a mother for her young boy, simply for peace for his little mind, go unanswered. The void of silence I’ve been screaming into with nothing but an echo strong enough to knock me down in return, has left me exhausted. And this sadness has absolutely leveled me.

//

This idea is, of course, not new. It’s actually a rather myopic view of life, of civilization, of the world, and I know that. Do I really think mothers have not been crying out to God for all of human history on behalf of their children, for a miracle to save their baby from starvation, the fever, the seizures, the wars? How many people of faith have pleaded for God to intervene only to watch the future they dreamed of slip through their fingers like fine grains of sand? We don’t tell those stories on testimony night at church. We rarely read them in bestselling memoirs. We are people who celebrate the miracle of healing, the only-God moments, the victories. We like those, we give standing ovations and raise our hands in worship for them.

The rest of life, the slogging through mud part, it doesn’t get much air time. It’s not as popular, lacks the shimmer and shine to be held up as admirable.

So no, this idea that prayers of great faith aren’t ever answered this side of heaven is not new.

Permission to speak freely? In the most real way, it is new for me.

I was certainly shaky and scared, but even as every waiting room of children with adaptive equipment and feeding tubes and loud noises gave me trepidation, I still ran into the disability world with optimism and hope and gusto. And I feel like I’ve carried those things mostly with consistency for the last eight years.

The gusto is gone. Optimism is elusive. And the hope, well, that’s hard to qualify right now.

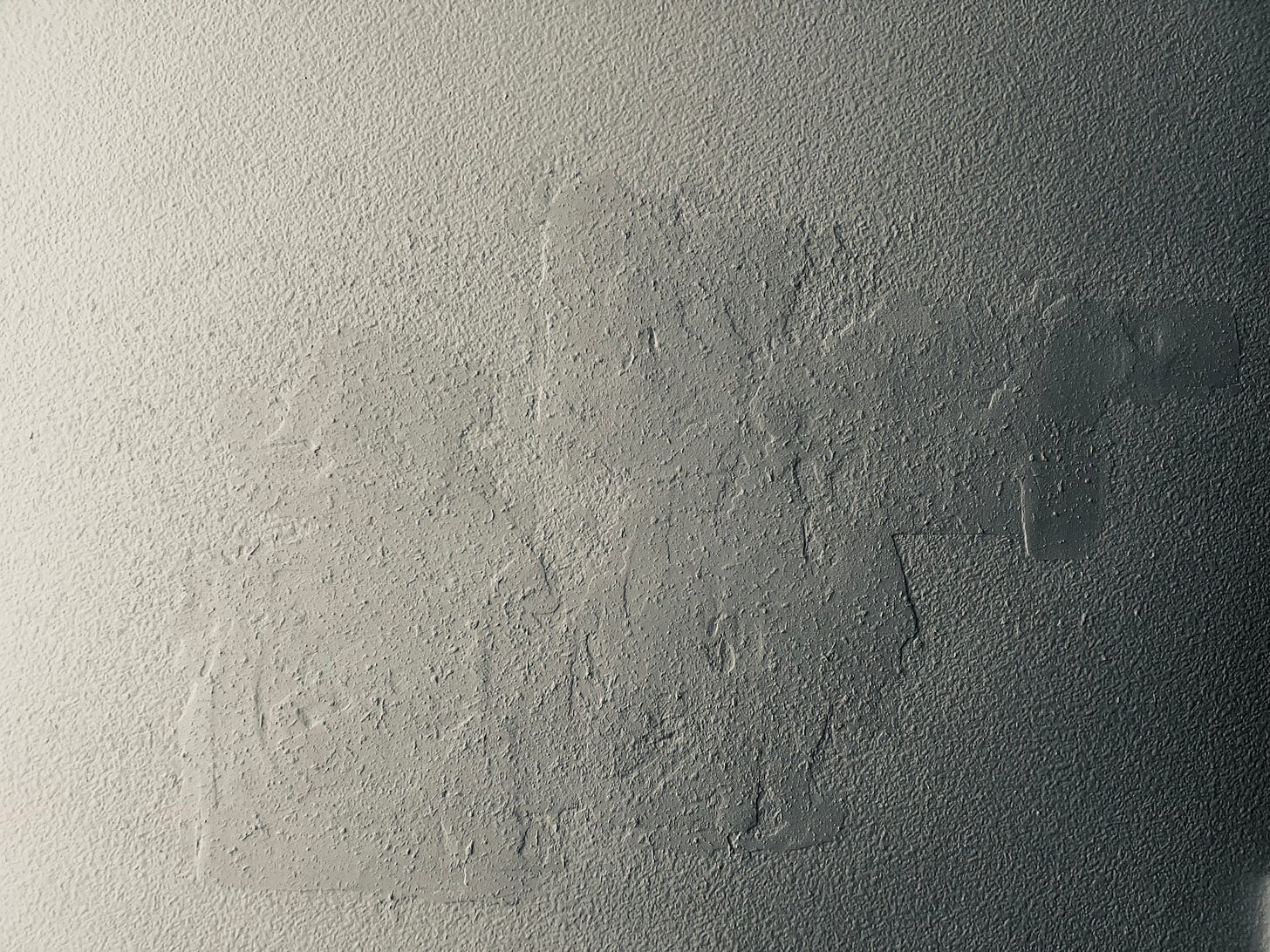

Last weekend, I patched 27 holes in the wall of our house, put there by the forehead of a little boy. I had conversations with his therapist about next steps when he gets even older and stronger, and no parent wants to think about those. I looked at my precious son in a spell of what I can only describe as madness, and I had absolutely no ability to help him. And I understood with a fresh perspective that this may very well be how the rest of our lives play out, patched together with drywall tape and spackling, doing its best to look like it was never damaged but finding that is impossible, because the holes I attempt to fix are always going to stand out a little.

But that’s too negative for testimony night at church, isn’t it?

//

I finished the 10-mile bike ride last night, and as I came up to my last turn before heading home, I could see the sunset directly in front of me, still golden, still perfect. I knew there was enough light for one more loop. My legs were tired, but they were okay, too, and knowing the kids were on the verge of bedtime and calm at home, and it wouldn’t trouble my parents for me to stay out longer, the moment felt right to challenge myself.

And not surprising, on my second attempt of the first hill of the loop, chest and legs begging for mercy, I was wishing I had gone straight home. But I lowered my eyes and tried to keep them on what was right in front of me, and I just kept moving. It was like my legs were saying to my heart and mind, “We will keep going if you do. But you have to go first.”

Someday, I really would love to tell you all about a miracle. About a little boy who hasn’t hit his head in years, who does many things independently, perhaps he even has a job! God is God, the one who spoke the rolling hills and baby quails and sunset into existence. He can do that for Cannon, and I still believe that. It hurts how much I believe it. Hope, man, the most beautiful, painfully vulnerable thing to have. But I will always leave room for the truth that there could be, perhaps, flourishing I cannot even imagine in the future.

But what if that is not the miracle I ever get to share? What if the miracle is that God holds my faith together even in the face of loss and challenge and pain I so naively thought my “good girl” status had safeguarded me from?

I don’t know, but I think if our hearts keep going first when life is always hard, leading the way when our bodies are so, so weary, that’s worth noticing, too. Maybe even worth calling miraculous.

😭😭😭 This is ruthlessly, generously, gut-wrenchingly honest and more powerful a testimony of faith than I’ve ever heard in a church. I love you. I love Cannon. Praying again and again and again and begging God for a miracle.

That was incredibly moving. I hate that you and Cannon have to endure painful things and honestly, that your enduring creates such moving and profound writing, but I’m also grateful that your ability to write causes me, and I’m sure so many others, to have immense empathy for the disability moms all around us. Reminding me to look up from my own mess to reach out to others who are walking tough roads - with hope.

Thank you for your writing Katie.